On January 11, 1992, John Thompson was an 18-year-old high school senior living on his family’s 1,600-acre farm near Hurdsfield, North Dakota. On that day, John’s parents were out of town visiting a relative in the hospital, leaving John at the home alone. After eating breakfast, John set out to take care of his chores on the farm.

He was using an auger powered by a tractor to move barley into the pig-feeding bins. He set the metal auger into place to feed the grain into the bins, then he parked the tractor next to the auger. The tractor’s engine powers another metal shaft, called a power takeoff, which sets the auger in motion, carrying the grain into the bins.

It was something he had done many times. But this time, John slipped or fell backwards into the takeoff. He remembers slipping on the ice, feeling a tug on his shirt – and in a terrifying moment, both of his arms were ripped off by the spinning machinery. The Thompsons’ power takeoff wasn’t fitted with a safety shield.

John was seriously injured, conscious, and alone. He made his way 100 yards uphill to the house. Unable to open a sliding patio door because it was locked, John used the bone sticking from his left shoulder to open the screen door at the front of the house. He then used his mouth to turn the doorknob.

John raced inside the house, and kicked in the door to the den. There is no 911 in Hurdsfield, so John dialed the first number that came to mind – his uncle, Lynn Thompson. He only lived a few miles away. After several failed attempts at dailing with his nose, John found a pen he could hold in his mouth. He used the pen to dial the number, and spat it out once he heard his cousin, Tammy on the other end.

“This is John. Call an ambulance immediately because I’m bleeding very bad and I don’t have any arms.”

John remembers repeating that, then hanging up. He wanted to clear the line so she could call the ambulance as quickly as possible. Once he had hung up, John made it to the bathroom and got in the bathtub – so he wouldn’t stain his mother’s carpet.

Tammy called her stepmother, Sharon Thompson and told her to call an ambulance. Next she phoned her mother, Renee Thompson, who runs a nearby gas station, and pleaded with her to quickly come pick her up and go out to the farm. They arrived at the Thompson farm in about five minutes. Once they got inside, they were greeted by splattered blood all over the home, and the sound of John crying in the bathroom. As Renee hustled in to comfort him, he implored her to keep Tammy away.

“It’s real bad, Aunt Renee.”

It took only a moment for Renee to realize just how bad it was. He was in the bathtub with the shower curtain covering most of him. For the next 20 to 30 minutes, she held John and talked to him, trying to keep his spirits up. John seemed mostly concerned with how others in his family would react to his accident, saying his dad would blame himself for leaving John alone.

He was very rational and alert, didn’t seem to be in pain, and he hadn’t lost his sense of humor. After Renee told him the ambulance would be there in a second, he promptly counted “1,001” and then said, “Well, it’s not here.”

When the emergency team got to the house, the volunteer crew of 2 women and 1 man had trouble concealing their shock. John directed the crew to garbage bags in the kitchen, and told them to retrieve his arms so they could be packed in ice.

After strapping John to the stretcher and packing his arms in ice, the crew sped to St. Aloisius Medical Center, which is about 20 minutes away. In the ambulance, John began experiencing phantom pain, complaining that his now severed hands were hurting. By this time, John had lost roughly half his blood.

What apparently prevented him from bleeding to death was the fact that the arteries had quickly closed off naturally, as if a tourniquet had been applied. The attending physician immediately phoned Van Beek, who was on call at North Memorial hospital, a regional trauma center that has six microsurgeons skilled in limb reattachment. At 3:30 P.M. John, accompanied by a doctor, lifted off from the hospital in Harvey aboard an air-ambulance plane for the two-hour flight to Minneapolis.

Speed was critical in repairing the damage, as it is in all limb-reattachments. Soon after John arrived at North Memorial, a surgical team led by Van Beek began working on his left arm, which had been severed above the elbow. Simultaneously, another team worked on the right arm, which had been torn off at the shoulder.

Experts say that the operation is not technically difficult, but it is a major trauma for the body. John underwent several surgeries after the initial one to remove dead skin and check the reattached blood vessels.

After having his arms reattached, he tried to regain some normalcy in his life. John went to school at the University of Mary, but he didn’t graduate. After about two years, he began touring and telling his story, talking about farm safety and motivating others to persevere. He gave that up in 1995, after the road wore him down physically and emotionally.

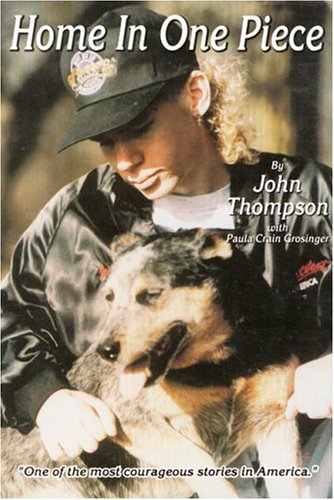

In 2002, he published a book called “Home in One Piece,” about his life. He wanted to put the accident behind him, but the book only made his life more hectic. John hit the road again, this time doing book tours, and his book became a bestseller in the Midwest.

He got into politics, which is something he had always enjoyed, and ran for the state House in District 40 in 2004. John said he dropped out, but was still on the ballot that year. He worked as a Realtor around 2008-2012, but he had trouble using keys and opening the doors of the houses he was showing. He often had to hand the keys to a client.

Things are more difficult for Thompson, but he still does them. He can’t button a shirt, but he can slip an already buttoned one over his head. He can’t write legibly, but he’s a better typist now than he was before the accident. And he can’t shake your hand, but he likes fist bumps.

John would like to get back into speaking or politics on a local level. Telling his story still gives him a purpose and makes him feel like he’s making a difference. That’s all he really wants: to help others, his mother said.

“Everybody needs to be needed, and that’s what he’s looking for,”

CITE INFORMATION:

2 thoughts on “John Thompson”